On Friday, May 2 of 1919, little Maude left by train for the Union Protestant Infirmary, part of Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore Maryland. She was only twelve years old and had never been so far from her Tennessee home, but she had her mother by her side to keep her safe on the journey. Maude would spend the next nine months in the care of the Johns Hopkins medical team with each professional working with the pre-antibiotic medical practices available during the early twentieth century.

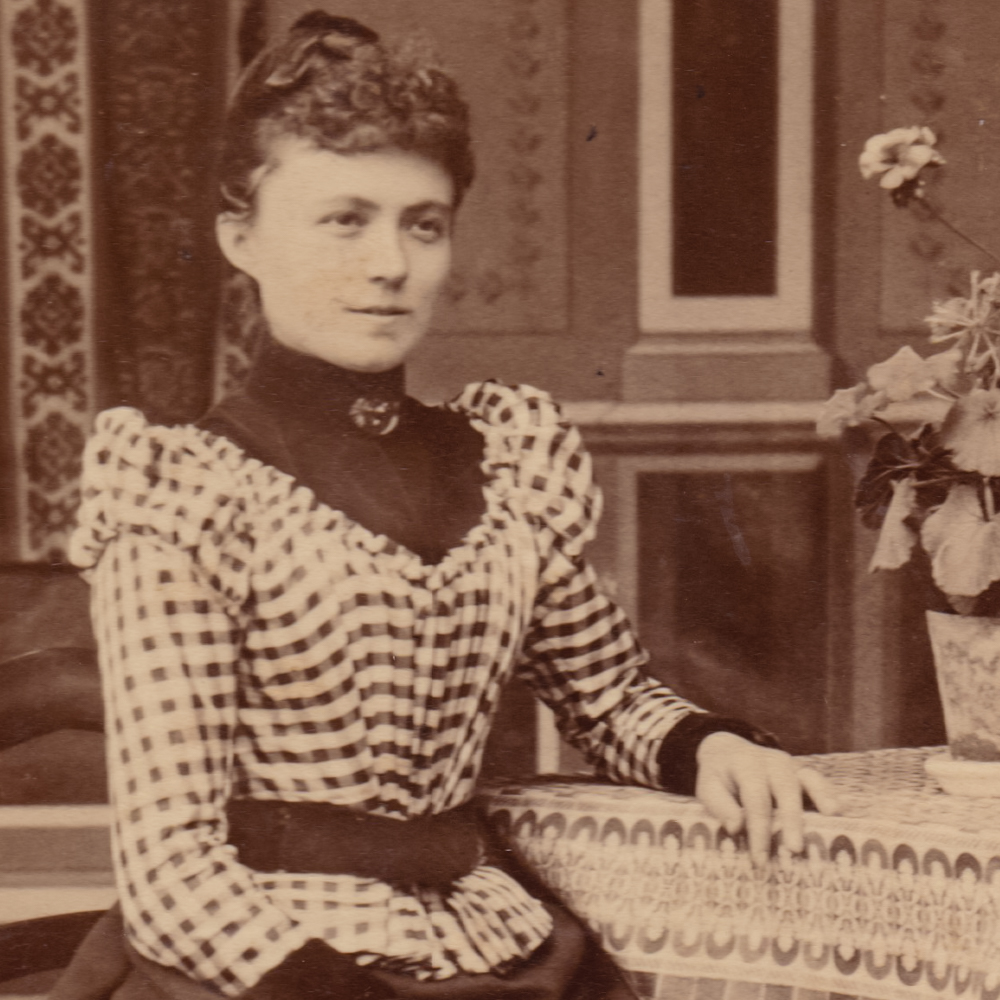

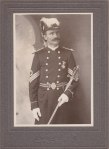

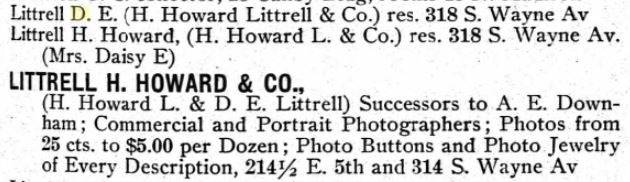

Ada Maude, referred to by her middle name by her family, was born the morning of July 10, 1906, in Washington County, Tennessee. She was the seventh of eight children of Lafayette Marion and Rebecca Emma (Toone) Payne. Maude’s mother Rebecca also preferred to be called by her middle name of Emma. And everyone who knew Layfayette called him L.M., which I imagine sounded like Ellem when being summoned by his wife. The L.M. Payne family set their roots in the rural Appalachian region of Johnson County, but later relocated to the nearby Pleasant Valley area of Washington County shortly before Maude was born. Their farm was located six miles from Jonesboro, “at the headwaters of the Big Limestone Creek.”1 Originally 132 acres were purchased, which later grew to 275 acres with the purchase of adjoining land.

The Payne family had recently lost their oldest daughter, Ruth Jane, to tuberculosis in 1917; she was only 21 years old when she passed away at home. So when Maude’s illness progressed from general weakness to paralysis, her family made the difficult decision to send her to Johns Hopkins for her care.

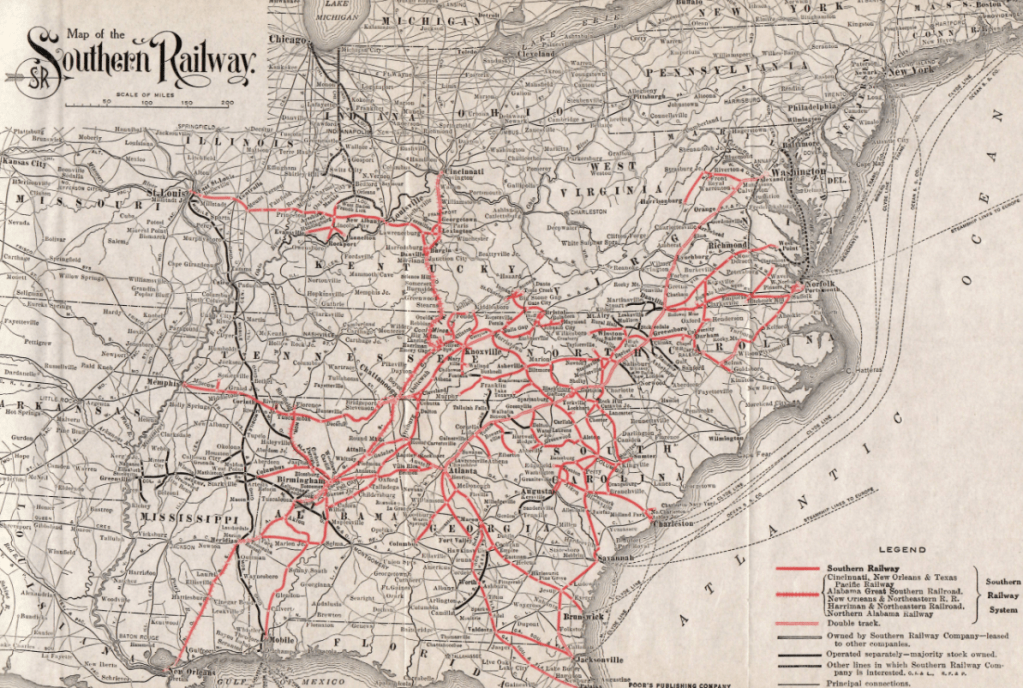

In 1919, passenger train travel was nearly at its peak and a central means of transportation for long distances. The automobile industry was just exiting its early brass car era and commercial airline travel was another ten years out. The Pullman Sleeping Car was a new addition to passenger train travel and was advertised as a “hotel on wheels,” promising comfort. Still, the 450-mile train journey to Baltimore would have been difficult for Maude in her current health condition. And she would need to travel by automobile to the nearest depot in Johnson City over unpaved roads to board one of the passenger trains.

Southern Railway built a new depot in the heart of downtown Johnson City in 1912 and became one of the primary passenger and freight systems in the area, offering more connections than the other stations.2 We don’t know if Maude took one of the Southern Railway trains to reach Baltimore, yet it seems likely. Making the 450-mile trip today by modern car would take most of a day, approximately 7 to 8 hours, not counting bathroom breaks. Traveling by a steam-powered train, with speeds around 40 mph and adding in several station stops along the way, it’s difficult to guess the timeline. A full day? Two days? And knowing 12-year-old Maude was in a paralyzed state, this must have been a grueling experience.

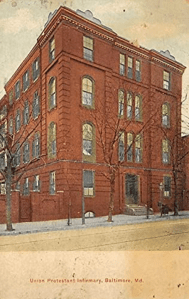

Maude was a patient at Johns Hopkins for nine months at the Union Protestant Infirmary, founded in 1854 as a charitable organization to provide medical services at no cost to families. Despite everything this business model suggests, Maude had a solid team of doctors and medical staff at this teaching hospital to give her the educated care she deserved.

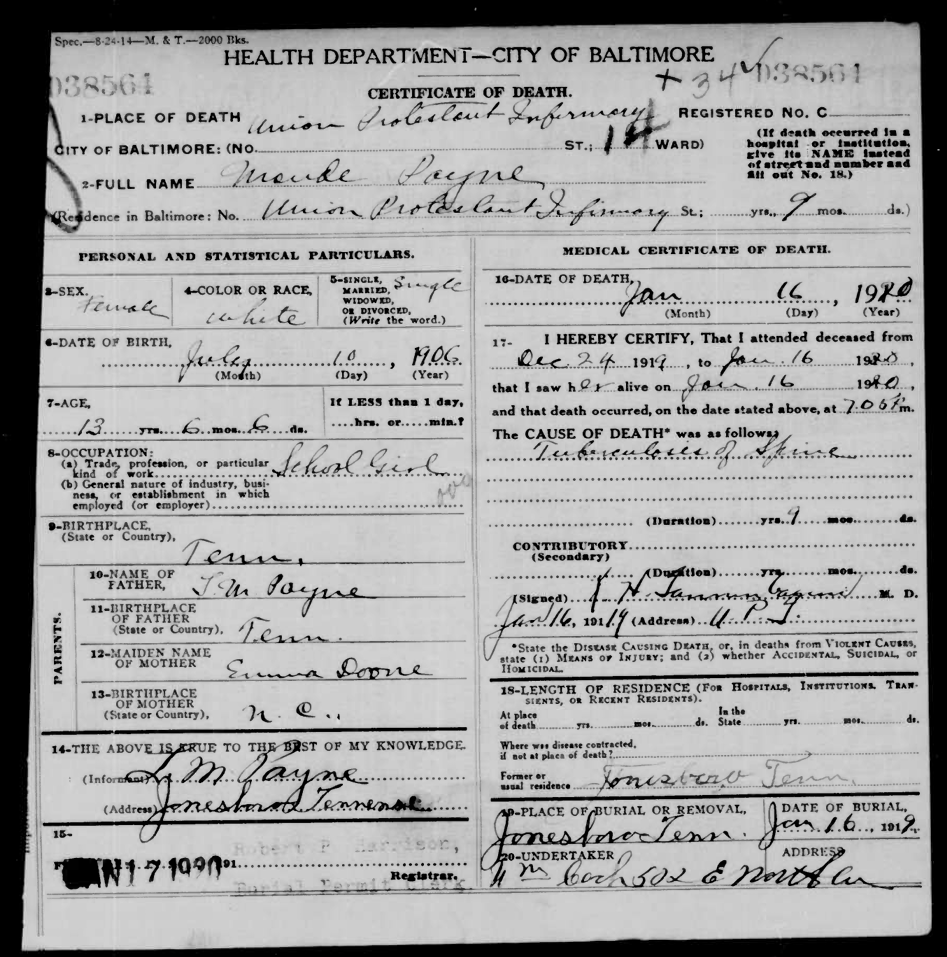

But it wasn’t enough. Sadly, little Maude died on the winter evening of Thursday, January 16, 1920 at the age of thirteen years, six months and six days. Her mother Emma later wrote a poem as a memoriam that was published in the Herald and Tribune in Jonesborough Tennessee on July 8, 1920 to narrate Maude’s health journey over those months. A story that reveals Maude’s bright light as she endured a crippling illness, as well as Emma’s tribute to the medical team.

In Memoriam

Maude Payne

One year ago the second of May,

We took little Maude away,

To the Johns-Hopkins hospital, the greatest in the land.

A band of doctors came around,

And with the X-ray the disease was found

Then Dr. Tibits said she would have to lie in bed,

With a weight to her little head,

And the paralytic would soon clear way,

And she could come home some day.

Dr. Bare took her in his care,

To give his students a share;

He would bring them around her bed

And turn and twist her head;

Then he would advise, just to make them wise,

So some day they can win a prize.

As weary months were passing by,

We watched with a wishful eye

For the U.S.A. mail to come flitting by;

Hoping a letter to receive that she was well again,

But it never came.

At last Dr. Nachlas wrote and to my regret,

Little Maude hasn’t improved any yet,

An operation is all that will do,

The paralytic to remove, if to this you consent,

So I boarded the train and to Baltimore I went,

And when the place I reached

Maude looked up with innocent surprise

With her beautiful blue eyes,

she said: “How is it that you have come again?”

And to this I did consent.

Then to the operating room she went

On a Monday morning soon,

And brought back in the late afternoon,

Again suffering many a pain.

Then in Doctor Nachlas came,

And called her honey, kiddy and pet,

And said, you will get well yet,

And we are so glad your mamma came

To help ease the pain.

You are the best girl I ever saw,

And soon you may go home to see your pa.

But Doctor Lee shook his head,

And said, long time you will be in bed.

She laughed with merry glee and said I’ll hide behind the door,

When I can walk and tease the nurses more.

Then in came Miss Mure

But no disease she could cure.

With sparkling eyes and shining grace

She said soon this little girl the nurses will chase.

At last a telegram came faster than the train through sleet and rain,

And said, Where is L.M.Payne?

Maude is very bad, and Oh! How sad we felt,

For little Maude was many miles away,

And we could not start until nearly day.

The train was late and before her father reached Baltimore,

A band of angels came and took her over

To that beautiful golden shore.

With her eyes closed and her face pale,

Ready to return to clay.

Miss Frantz, so saintly sweet,

Came across the icy street,

The doctor had said Maude is very ill;

And she came a mother’s place to fill.

It was God’s will to take her away,

At the close of that day.

Written by her Mother.

The Jonesboro Herald and Tribune (Jonesborough Tennessee), Thursday, July 8 1920, page 8

A family friend later shared that as Maude was dying, she said these words to her nurse, “I am going to sleep now, to sleep that long, sweet sleep. Asleep in Jesus, oh how sweet, where none ever wake to weep.”3 Maude recalled these words from a Christian hymnal “Asleep in Jesus! Blessed Sleep.”4

Ada Maude Payne is my great-aunt as these things go. My maternal grandfather’s little sister. My grandfather, Fred Payne, was only 15 years old when Maude died. Family lore has it that Ruth Jane’s early death by tuberculosis held an impact to the family, but Maude’s passing was the impetus to generational trauma. My mom tells us that our grandfather Fred was vigilant in inspecting every tuberculosis test on his four children to ensure they would not suffer from the past.

So what was little Maude’s cause of death? Emma’s memorial poem suggests many of the health concerns of the early 21st Century, from the Great War’s Spanish Influenza to Polio to Tuberculosis. But really, none of those hit the mark for a diagnosis.

Because Maude’s death was in Baltimore, I contacted the Maryland archives for any records available. We successfully discovered her death certificate showing her cause of death to be Tuberculosis of the Spine, also known at Pott’s Disease.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a rather familiar disease. It exists still today, but tends to be considered an “old-timey” affliction. We’ve all heard the historical stories about consumption and infirmaries designed to quarantine patients. But Tuberculosis of the Spine was different. A diagnosis was grim in the early twentieth century, associated with a high morbidity rate and the double hit of neurological deficit and spinal deformity as the worst complications. 5 Prior to today’s anti-tuberculosis therapy, there was no consensus on the management of TB spine and depending on the practitioner it was managed either conservatively or with surgical debridement.6 Surgery would be performed to remove abscesses, but little could be done to treat the disease as it progressed.

We find some of those clues in Emma’s memorial poem. An x-ray to confirm diagnosis, weights as an attempt to correct the spinal deformity, an optimistic surgery, followed by a rapid decline, possibly accompanied by sepsis. Her health deteriorated so quickly that Maude’s father sadly wasn’t able to arrive in time after receiving the telegram.

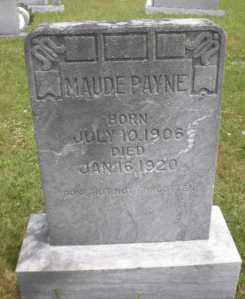

Maude’s remains were returned to Tennessee where she was interred at Pleasant Valley Cemetery in Washington County.

Because our little blue-eyed Maude left to run free on “that beautiful golden shore” so young, she has no descendants to pass along her story. And everyone who knew her is, of course, gone now as well.

I feel it’s important to share the story of our relatives that would otherwise simply be a dash of Date of Birth-Date of Death in our family tree. And I’m glad we can do this for Maude.

- The Payne Family Record, Mary Nell Payne Lee, 1972 ↩︎

- Archives of Appalachia, accessed July 19, 2025, https://archivesofappalachia.omeka.net ↩︎

- Maude Payne story of her hospitalization at Johns Hopkins and death.

Article from Feb 12, 1920 Herald and Tribune (Jonesborough, Tennessee) Stories and events, Human interest ↩︎ - https://christianmusicandhymns.com/2022/09/asleep-in-jesus-blessed-sleep.html ↩︎

- Jain AK. Tuberculosis of the spine: a fresh look at an old disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Jul;92(7):905-13. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B7.24668. PMID: 20595106. ↩︎

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-9495-0_2 ↩︎