The City of Dayton, Ohio in 1867 was at the edge of the second industrial revolution and maturing from her agricultural beginnings. Factories were competing for prime real estate along the new railroad lines to transport their goods faster and cheaper than ever before. And as one of the largest Ohio cities, immigrants arrived by the hundreds in search of employment and with romantic hopes of achieving the American Dream they’ve heard so much about.

Meanwhile in Ludwigsburg, Germany, Adolph Otto Moosbrugger was struggling to rise above the poverty of his youth. The first-born son of a country doctor and a French refugee, Otto referred to his early childhood as “happy and gay, although always hungry.” His earliest memories were of scarcity and rationed food. He later tells of respect for his mother, Josephine, in how she would split a small loaf of bread among six hungry mouths without giving a preference to any one person.

In 1860 Otto turned 21 and joined the military when the Kingdom of Austria, an ally of Germany at the time, went to war against Italy. After the war, he left the military as rank promotions were slow during peacetime and he then moved through several clerical jobs, but never making much money. It was when working as a bookkeeper at a cigar factory in Mahlberg that his life began to take focus. Otto began courting 18-year-old Wilhelmina Föhrenbach, who also worked at the factory. Surrounded by the aromatics of tobacco and sweat, the two fell in love. They wanted to marry, but Otto knew his clerical career wouldn’t provide the income need to start a family.

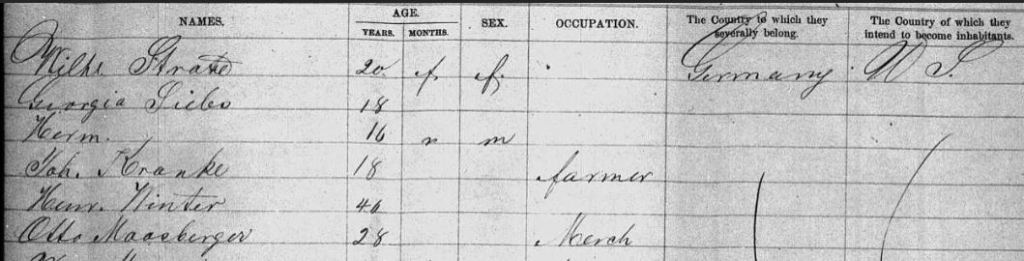

A good friend of Otto’s, Gustas Dreher, was a brewer in Mahlberg and had spent several years in the United States. He would tell Otto glorious stories about this Promised Land, “portraying it in the rosiest hues.” With a plan in mind, a 28-year-old Otto bought passage on the steamer, “New York,” and made a promise to send for Wilhelmina when as soon as he could.

Twelve days after leaving Germany behind, the ship arrived at Ellis Island on a cool fall day to deliver her passengers to this new world. With his next step fully decided, Otto continued his travels to the renowned city of industry, Dayton, Ohio.

Otto was bilingual, being fluent in German and French. However, he couldn’t speak a word of English. He was challenged by this language barrier, especially when trying to find work. He began with labor jobs, such as painting railroad cars for the Barney & Smith Company. He enjoyed the physical work, which he felt held more respect than clerking. But he was frustrated in the low wages that kept him from his goal of bringing Wilhelmina from Germany. In Otto’s words, he was “unable to earn even the salt for his soup.”

As the labor force grew in Dayton, so did the trade union movement. Many unions had a strong discrimination against immigrants, making higher paying labor jobs outside of their reach. Otto eventually found a better paying job with a German-owned music store as a clerk. After two years, he finally had enough money to send for Wilhelmina. They married in 1869, and moved into the second story of a home at 24 Buckeye Street that was owned by an elderly couple, the Wiedman’s, who lived on the first floor with their adult son.

The German American population in Dayton during this time was nearing its peak. According to Linn Orear’s Survey of the Germans of Dayton 1830 – 1900; their cultural and economic role, by the year 1890, eleven percent of the city’s citizens were of German heritage, with many other Germans living in the surrounding areas. By 1900, the German-born living in Dayton far outnumbered natives in the occupations of bakers, butchers, and brewers.

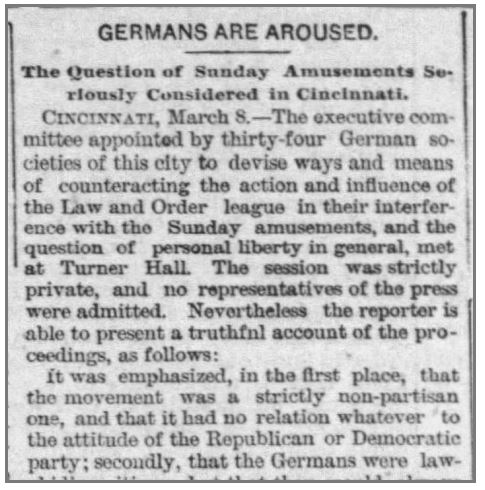

Because of this large immigrant population growth, nativism supporters were very active in cities across the United States. Nativism was supported by followers of the “Know Nothing Party,” who were political activists rebelling against those who were bringing foreign ideas into the communities. The Know Nothings were against the Irish for practicing Catholicism and they didn’t like the Germans, accusing them of cultural isolation, and their implied superiority and aloofness. Nativism methods ranged from petitions and legislation, but eventually escalated to violence. City riots in large cities were common, sometimes triggered by something like when the German community insisted on celebrating Sunday with parades, picnics, and songfests, when the Know Nothings felt Sundays were to be treated as a solemn day of peace and rest.

Otto was engaged with the political activities in Dayton and was compelled to protect the German community he lived in. By 1875 he had reached a self-taught fluency in the English language. He took a job as a treasurer with a tri-weekly German language newspaper, intending to support the German American citizens in that role. The paper was so poorly managed by its editors, however, that many times they couldn’t even make payroll.

It was time for a new plan.

[continued at Otto and his German Language Newspaper: Part Two]

Sources:

- Moosbrugger, Adoph Otto. Personal Life History of Adoph Otto Moosbrugger. Handwritten Journal, 1909

- Orear, Linn. Survey of the Germans of Dayton 1830 – 1900; their cultural and economic role. Thesis. Miami University, 1961

- Paasche, Gottfried. America, Germany, and the Daytoner Volkszeitung 1880-1900. Thesis. Miami University, 1961

- Rattermann, H. A., and Elfe Vallaster-Dona. German Pioneers of Montgomery County, Ohio: Early Pioneer Life in Dayton, Miamisburg, Germantown. Published for Clearfield Company by Genealogical Publishing Company, 2014

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich, et al. German Immigration to America: the First Wave. Heritage Books, 2007

- Wittke, Carl Frederick. The German-Language Press in America. Literary Licensing, 2000

One thought on “Otto and his German Language Newspaper: Part One”